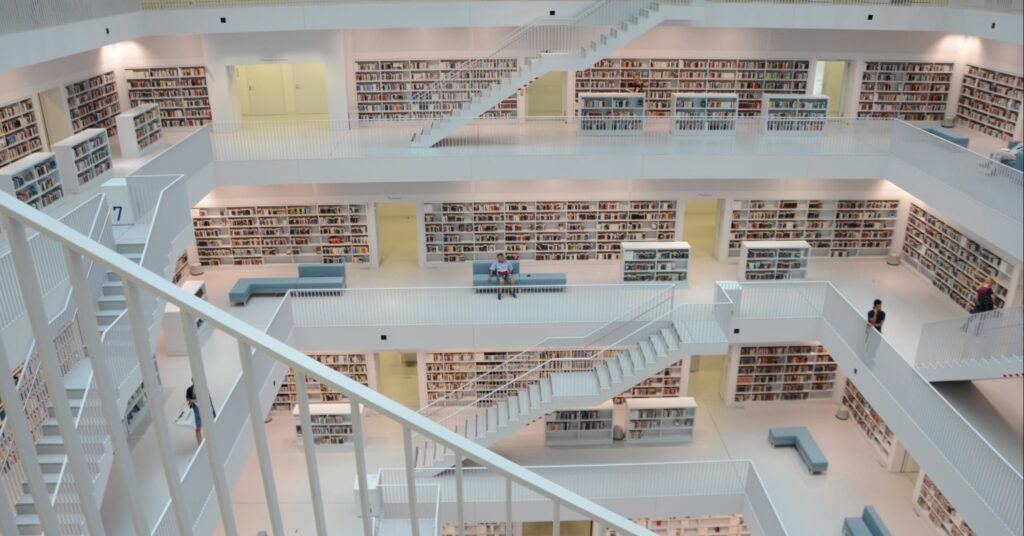

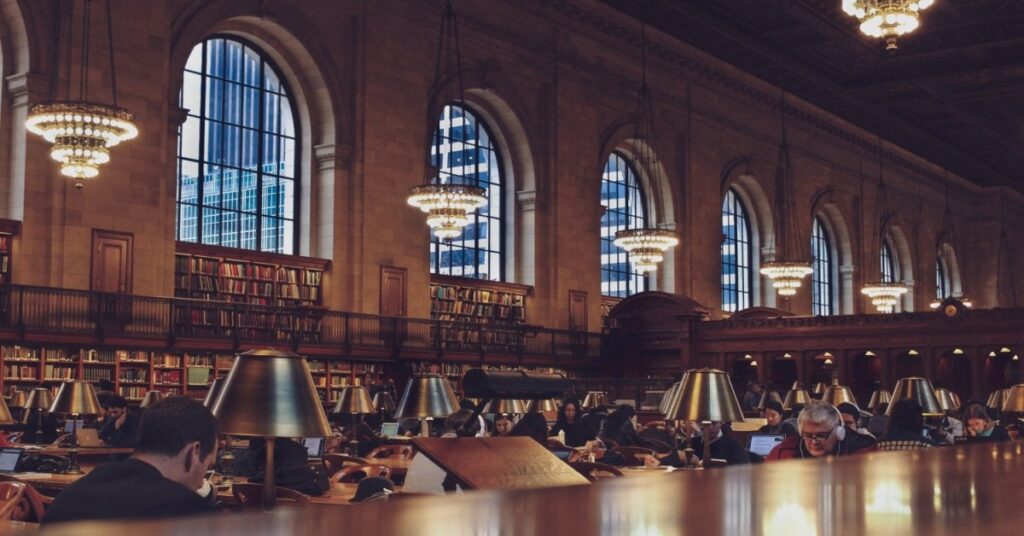

What Is a Master of Library and Information Science?

all LIS professionals must be information-literate. They can work in [...]

I’m not even sure why I picked up the phone.

Typically, I hang up as soon as I know it is going to be a sales pitch, but this one was different. It was from my alma mater, Azusa Pacific University. APU was exhorting alumni to update their contact information for a networking book that would allow graduates of various years to get in touch with one another.

It sounded harmless enough, so I gave the benign voice on the other end of the line my details. As she was inputting the data, she remarked about how wonderful it was that I was a special education teacher — and in the very same breath how awful it was that some people were trying to place students with disabilities in general education classrooms. I guess she assumed I would agree.

“Sorry to burst your bubble, ma’am, but I’m one of those people,” I said.

Why would someone have a problem with students with disabilities being educated side by side with their non-disabled peers? For those of us who are involved in special education, or those who have observed student learning, it is easy to see that inclusive classrooms work. For almost everyone else, it appears to be a near-impossible concept to grasp.

I fear that an unintended consequence of the creation of special education services is that they have become synonymous with separate education services. Since the passage of PL 85-905 (which authorized loan services for subtitled films for the deaf) and PL 85-926 (which gave federal funds to train teachers to work with people with intellectual disabilities) in the 1960s, the federal government has taken an active role in special education.

Around the same time about half a century ago, families began to institutionalize their severely disabled family members. Though this became less acceptable over time (as families have become less dependent upon segregated institutions and more dependent on community-based living and learning), the damage had been done. Just as the country had awoken to the realization that people with disabilities deserve an education and a living space, it nevertheless did not know how to provide these things within the context of the broader non-disabled world. So the government created separate systems. This wouldn’t be so bad if these separate systems had changed to evolve with our culture’s current attitudes toward civil and disability rights, but that’s not the case.

| University and Program Name | Learn More |

|

Merrimack College:

Master of Education in Teacher Education

|

What we have today are fragments and pockets of schools and communities that “do” inclusion well. The vast majority of places, however, are either unwilling to implement inclusive classrooms or lack the resources to know where to start.

Some schools, however, are leading the way for how to do inclusion right. CHIME Charter School in Los Angeles, for example, has been a leader in inclusive practices for more than 25 years. As the school’s executive director explains, CHIME provides instruction for three groups of learners, “typical, gifted, and those with special needs,” all in a general-education setting. This integration entails providing the “supports, services, and educators” necessary to help all students.

What makes CHIME different from other schools? Its focus on all students. Research has shown that when the focus is on the aggregate of students rather than on those with special needs, everyone benefits.

Studies and surveys on inclusive education seem to conclude that students with disabilities stand to gain a lot from placement in general education settings. In addition, those without disabilities may see better outcomes, too.

“But isn’t special education working?” you might ask. It depends both on your expectations and on how you define “working.” Speaking from experience as a special education teacher in a self-contained setting, I can say that rarely do students ever graduate or “get out” of special education (i.e., because they no longer qualify for services). Nor do they catch up with their grade-level peers when they’re kept in a special education setting. Typically only the students who demonstrate a major improvement in intellectual ability (as evidenced by test scores) are pushed into general education classrooms. Unless a special education teacher or parent is proactive in asking for a child to be switched into general education, this won’t happen.

What this means is that students with intellectual disabilities, autism, or developmental delays are relegated to multi-grade classrooms in which teachers are forced to move at a much slower pace than should be necessary. In situations like these, teachers are usually only able to cover a small portion of the appropriate grade-level curriculum for each student. In my opinion, there is a better way of educating our kids, and it must start with the understanding that we have to cater to all learners.

Imagine there’s no special education — nothing “special” or “separate.” Every teacher gets the same training as every other teacher. We must remember that those specialized instruction strategies that we are supposed to use with “special ed” kids — well, it turns out, they are good for everybody. Those visual aids and reminders and those time management strategies that are great for kids who are on the autism spectrum — it turns out they’re great for everyone else, too! Having clear, positive, and reasonable expectations for students considered to be disruptive — those practices are good for everyone, as well. Then there is the money. Instead of special ed money and general ed money, there should only be education money, and it should help all students.

Sounds like a perfect world, doesn’t it? Perhaps it is. But the one thing that makes me hopeful is that there are examples of this very thing happening all over the country and the world. I’d love for us to follow the examples that some schools have already begun to set. It’s the right thing to do to help every child learn.

Read more from Tim Villegas and other education experts in special education. Sign up for a free Noodle account to ask questions about any school’s policies.

Sources:

Cole, C. M., Waldron, N., & Majd, M. (2004). Academic progress of students across inclusive and traditional settings. Mental Retardation, 42(2), 136–144.

Cushing, L. S., & Kennedy, C. H. (1997). Academic effects of providing peer support in general education classrooms on students without disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 30(1), 139–151.

Kalambouka, A., Farrell, P., & Dyson, A. (2007). The impact of placing pupils with special educational needs in mainstream schools on the achievement of their peers. Educational Research, 49(4), 365–382.

Kurth, J. A., & Mastergeorge, A. M. (2010). Academic and cognitive profiles of students with autism: Implications for classroom practice and placement. International Journal of Special Education, 25(2), 8–14.

Ruijs, N. M., Van der Veen, I., & Peetsma, T. T. (2010). Inclusive education and students without special educational needs. Educational Research, 52(4), 351–390.

Sermier Dessemontet, R., & Bless, G. R. (2013). The impact of including children with intellectual disability in general education classrooms on the academic achievement of their low-, average-, and high-achieving peers. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 38(1), 23–30.

Sermier Dessemontet, R., Bless, G., & Morin, D. (2012). Effects of inclusion on the academic achievement and adaptive behaviour of children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 56(6), 579–587.

Questions or feedback? Email editor@noodle.com

all LIS professionals must be information-literate. They can work in [...]

Elective courses can customize your MLIS degree to a career [...]

Do you intend to work in your community's public library [...]

For decades now, libraries have been attuned to new developments [...]

A more diverse teacher workforce could provide a key to [...]

Categorized as: Special Education, Education & Teaching